Climate, Class and the Culinary Arts

Climatic fluctuations play a crucial part in shaping our food consumption and our modern politics. From the School of History, Dr Claudia Kreklau‘s research discusses how climate change induced famine shifted the diets of Central Europe in the early to mid-19th century, leading to political protests in an already-changing society. Her work reveals that the middle class — previously believed to have eaten nutritionally dense diets — combined the need to survive on rotten food, scraps, and bread with the desire to eat like elites all over Europe.

The famine of the early 19th century exacerbated existing social injustice across Central Europe. Born from the climate catastrophes of two volcanic explosions in 1809 and 1815 which spread a sulphuric acid cloud across Asia and Europe in the early 1800s, the cold decades and wet summers reached Europe, causing harvests to rot on fields and grain prices to fluctuate. The consequences of this were profound and felt across classes. Elites made financial losses, the middle class only just managed to get by on ever-worsening food, while those at the bottom of the social spectrum either could not afford food, or else suffered hunger. Climatic changes between 1800 and 1850 effectively caused lasting changes in the diets of central Europeans, where while elites hoarded luxurious meals, the middle and working classes struggled and invented new ways to make it through the winter. All this sparked civil unrest.

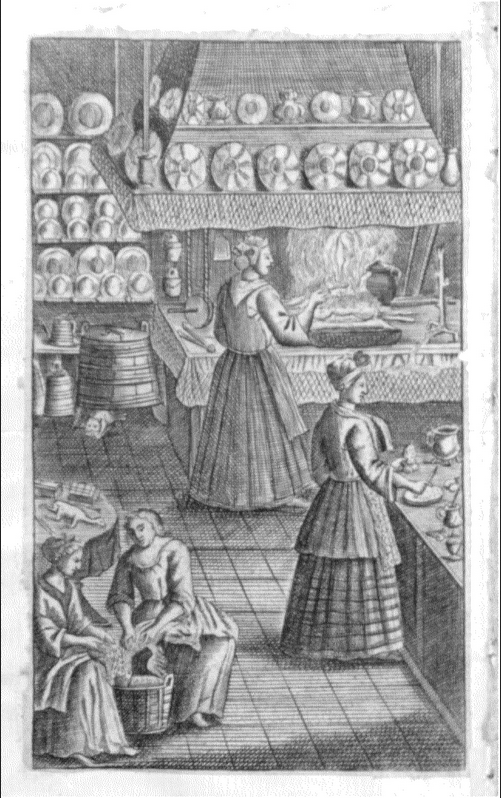

Worker poverty was systemic and built into the class structure that surrounded him. Men employed in rural work were fed by a “Speisemeister”, a Master of Food, who determined labourer’s diet in composition, quality and quantity. Despite this, their food was not free. Peasants paid for the luxury to get nutritionally low and monotonous meals from a Speisemeister and had little choice or say in this period of scarcity. Their diet consisted almost entirely of carbohydrates, meat was served just once or twice per week. Vegetables, fruits, and healthy fats were scarce. Working intense days, peasants had access to 1500- 2000 kcal per day, unless they managed to supplement this with home- or field-grown fruits and vegetables. Food theft rose significantly in this era and life expectancy was around 40 years.

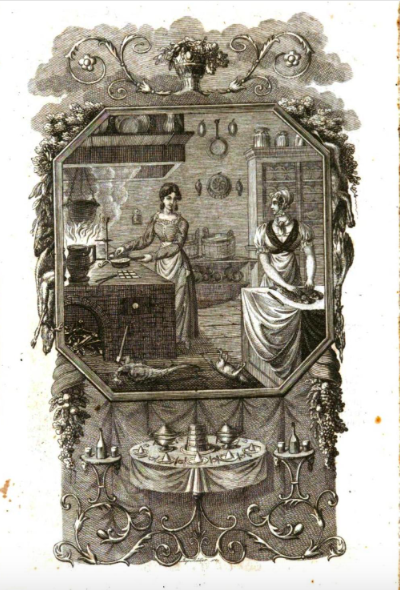

Dr Kreklau has revealed much about how the middle class ate during the 19th century, reshaping previous beliefs that the middle class ate satisfying diets. The reality is that they kept eggs for a year, meat until it turned green (when they treated it with chemicals to give it a red hue) and worked all year to survive the cold season. Much of their food was pickled and jammed, as well as boiled with juice and vacuum-sealed based on household understandings that air could spoil food. At the same time, the middle class ate aspirationally toward elite living standards, bought cook books written by the chefs of the elite, or hired cooks trained in royal kitchens, whenever they could afford it. They ate British dishes, approximations of Mexican, French, and Asian-inspired cuisine, and adhered to basic vegan and vegetarian diets when industrialists began cramming their products with substitutes and additives. Dr Kreklau proposes that this combination of practical thinking, household-innovation for preserving foods, and cosmopolitan outlooks and simultaneous acceptance and scepticism of industrially-produced goods made German 19th century middle class consumers among the first modern eaters.

Protests

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, farm labourers, the poor, and working-class individuals ritualized protests for grain and food. Both rural and small-town populations viewed bread as the body of Christ, something which they have a right to possess in order to survive, and deployed religious imagery to communicate dissatisfaction to elites. In the 19th century, these protests evolved to encompass explicit political rhetoric inspired by the French Revolution of 1789. With socialism’s rise on the horizon, working classes demanded better living conditions and chances for survival, while the middle class demanded to have access to vote and to visit libraries, the right to free speech, and universal education. The revolutionary protests for reform in 1848 united individuals across the social spectrum, agreeing in their general discontent, though entirely at odds with regard to political programs, economic priorities, or social visions.

Similarly, economically, socially, and politically hybrid demonstrations continue to operate in Germany today. Protests against pandemic measures in 2020 brought together a range of unlikely companions, from early-childhood educators worried about their students’ social development, to radical right-wing voters with aspirations to idealize Germany’s authoritarian past.

Kreklau’s research reveals how the relationship between people and their food provides insights about their class, lifestyle, culture, and politics. Through understanding how climate can impact our eating, Kreklau’s work thematizes the connections between climate, economic crises, protests, and the aspirations of modern consumers to lives of security and comfort in a changing world.

Read about Claudia’s research on the history of food adulteration here