Using Participatory Action Research to address the supply and demand sides of unprescribed antibiotics in Tanzania

Understanding the socioeconomic and psychosocial drivers of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) is vital if we are to prevent this potential global health catastrophe. AMR is a burgeoning healthcare crisis wherein bacteria, fungi and other pathogens develop an immunity against antimicrobials (a collective term for antibiotic, antifungal, antiparasitic and antifungal drugs). If a solution to this crisis is not found, more than 4 million people across Africa, and 10 million people globally, could die by 2050 and many more face long and expensive illnesses. This is not only a threat to global public health, but also to economic development; it is estimated that countries within Africa could lose 5% of their GDP because of this crisis, a deeper toll than the 2008 financial crisis.

In many Low- or Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) like Tanzania, it is very common for people to access antibiotic drugs without prescription, and to fail complete recommended minimum courses. These conditions offer pathogens opportunities to evolve resistance to drugs that would normally kill them, leading to the prescribed medicines becoming ineffective. Consequently, infections that should be treatable via a course of antimicrobials become prolonged illnesses that even prove fatal. Whilst pharmacological research continues in the search for drugs effective against the more resistant strains, interdisciplinary research at the University of St Andrews within the ‘Holistic Approach to unravel Antibacterial Resistance (HATUA) in East Africa’ project under the leadership of Professor Matthew Holden from the School of Medicine, has been combining insights from microbiology with those of social science colleagues from the School of Geography and Sustainable Development (SGSD).

In the latest initiative in this highly successful collaboration, Dr Mike Kesby and Dr Kathryn Fredricks (SGSD) build on the findings of the consortium’s earlier work to pilot an intervention that seeks to address both the supply and demand side of unregulated over-the-counter antibiotics sales using participatory citizen science. They are partnering with the Catholic University of the Health and Allied Sciences, the Tanzanian Ministry of Health, the Tanzanian Pharmacy Council and the award-winning grassroots NGO Roll Back Antimicrobial resistance Initiative in this ‘Impact- oriented’ project.

Whilst a regulatory framework for prescribed dispensing exists, (imperfect) market forces ensure citizens frequently demand drugs they do not need, and take them ineffectively, and sellers supply drugs they should not sell because they fear that if they don’t others will. Stricter regulator enforcement is expensive and logistically difficult and under-values seller’s genuine desire to serve communities who face numerous challenges in accessing existing healthcare systems. Drug dispensers and users need to be engaged simultaneously; the public needs a better appreciation of the effective use of antibiotics, and what constitutes good service from a seller, and sellers need a commercial motivation to pursue better antibiotic stewardship and advice-giving.

To address this issue, Kesby, Fredricks and their team set out to open dialogue with policy makers, practice groups, drug sellers and communities to create cost-effective ways to intervene in the supply and demand sides of the drug sales market. They propose a three-part strategy:

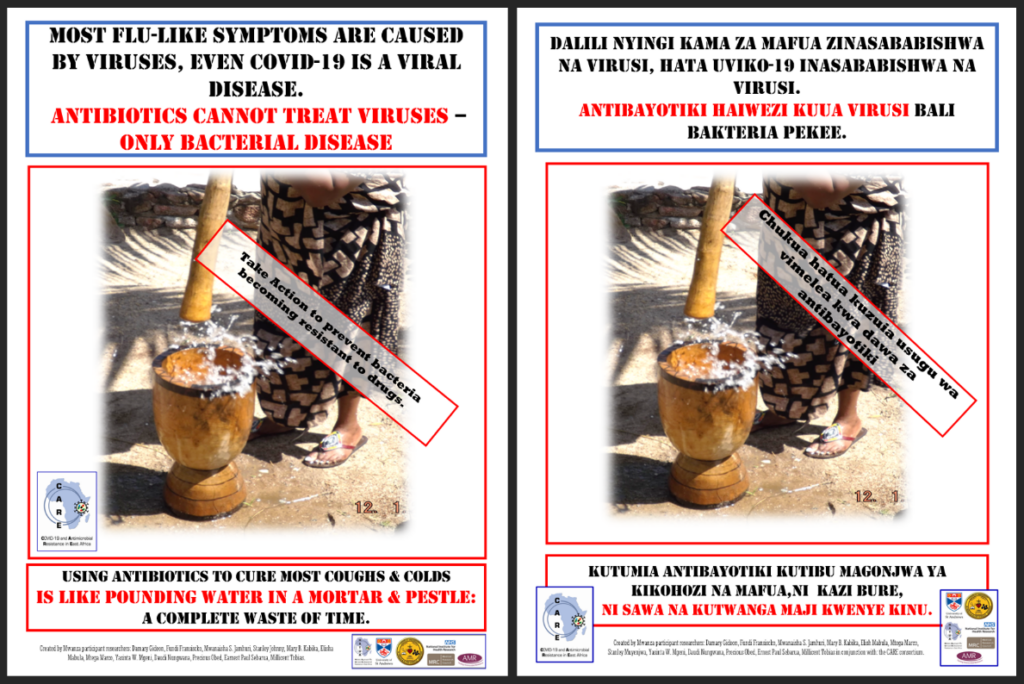

First, they will continue to develop their strategy of creating public health information on antibiotics and AMR, that is codesigned with and accessible to grassroots communities. These will be distributed in the intervention communities as traditional and social media products and include, posters and audio-visual materials designed to inform them of the dangers of using antibiotics inappropriately and to accept the stewardship advice of good sellers when the give it. Following successful engagement with stakeholders in Tanzania, many of these materials have already been distributed during the 2022 AMR awareness week. Furthermore, the AMR lead in the Tanzanian Government has also requested for the materials and information generated by the team to be distributed in hospitals and other public health spaces across the country.

Second, as antibiotics are almost never identified as such when they are being dispensed, they are providing participating pharmacies with easy-to-use stickers to be applied to antibiotics to help spread awareness in communities of which drugs fall into this category. Both poster and antibiotic stickers will utilize QR codes that provide further information on AMR and proper antibiotic use.

Third, they have repurposed ‘mystery shopper’ research methods as an ongoing surveillance system. Sellers will know that, but not when mystery shoppers are visiting. Those that perform consistently well on improved antimicrobial stewardship and good advice to customers will be presented with bronze-to-gold certificates of good performance, accredited by the Tanzanian Pharmacy Council. The public will be advised to patronise those sellers who received these certificates, giving sellers a commercial incentive to pursue improved practice.

This adapted methodology represents a shift towards the seemingly contradictory notion of ‘participatory surveillance’. Local citizens, and pharmacy students in training, using epicollect5 on their mobile phones, conduct regular survey sweeps of local drug sellers to monitor their dispensing and advice giving. This has the potential to further empower local communities to encourage quality service from providers as well as produce a low budget system of monitoring to augment the existing formal pharmaceutical inspection system. Furthermore, were such monitoring to become an element of the pharmacy curriculum then the long-term impacts and practical sustainability of the approach would be further increase.

Kesby and Fredricks have been exploring the possibility the development of an app, that would allow citizen to access a list of ‘trusted pharmaceutical traders’ generated from the ongoing monitoring data and good advice on antibiotic use, and perhaps even to in-put data based on their own experience. Working in collaboration with the School of Computer Science, they have co-supervised a project by MSc students that modelled various prototypes for an app design. The project is also supporting a PhD Sustainable Development student, with the longer-term goal of exploring a project based on similar themes in Nigeria.

Impacting appropriate antibiotic dispensing in Tanzania works in accordance with the Sustainable Development Goals, including that of good health and wellbeing (SDG3) and peace, justice, and strong institutions (SDG16). The project model will pilot a means to give drug sellers a commercial incentive to better align themselves with existing policy, thus aiding larger institutions in ensuring their subsidiaries are compliant. It has the potential to empower citizens to demand higher quality health advice and service and combat the injustice and resulting health inequalities related to being sold drugs which they do not need or know how to use appropriately. The work of this team contributes to the challenges developing practical means to prevent the development o