Woven Communities

A century ago, there were several thousand traditional workshop basket-makers in Scotland. At this time, baskets were an essential tool for domestic, social, and economic life, including in fishing, farming, and home-building. Dr Stephanie Bunn, from the Department of Social Anthropology, notes that “they were used to carry or contain peats, seaweed, bait, fishing lines, fish, tatties, animal fodder, fleece, and so much more.” Today, the number of traditional basket-makers is perilously low, and there are concerns about the cultural value they maintain being lost altogether.

Like many practical skills, the value of basket-weaving is not only cultural. The project Woven Communities, led by Dr Bunn, has expanded awareness of Scottish social history and heritage through a focus on its basket-weaving, while showing how practical craft- and hand-skills, such as basket-making, can play a key role in cognitive development and can both enhance mathematical skills, and even slow cognitive decline. Her new project, Forces in Translation, has developed out of this aspect, and focuses on craft and mathematical cognition: between them, the two projects have a wide array of partners that include the Scottish Basket-makers-Circle; multiple Scottish Museums and galleries; Stroke Recovery Unit, Raigmore Hospital, Inverness; University of Hertfordshire, University of Aberdeen, Manchester Metropolitan University, University of Aarhus’ Centre for Future Technologies Culture and Learning, the Basket-makers Association, and the Worshipful Company of Basket-makers.

Publication of Bunn’s research includes work on basketry, design and recovery in the Journal of Design History, Craft Research and the Journal of Art and Communities, and two definitive edited volumes, Anthropology and Beauty and The Material Culture of Basketry, both of which bring together a diverse array of scholarship on artistic and material culture that move beyond the aesthetic and approach a deeper understanding of what these highly nuanced topics mean to individuals. The first volume focuses on the theme of beauty, inviting readers to reflect on their own ways of understanding and engaging with beauty in all its diversity. This paved the way for the latter anthology, which focuses on basket-weaving to demonstrate how local knowledge of materials and place is essential to the craft and, by extension, artistic expression itself.

The importance of local knowledge has informed the vital impact work with which Bunn has complemented her research. From 2010, Woven Communities has worked with the Scottish Basket-makers Circle, using practical basket-work to enhance understanding about Scottish cultural heritage through the lens of basketry, a key fabric of society in crofting, farming, fishing, transport and industry until the 1960s. Through practical events, the researchers elicited new knowledge about Scottish social history, improved the understanding of museum basketry collections, explored the intangible cultural heritage in these collections and communicated their research to the public. By taking the basket, an essential, everyday artefact, as their central research focus and using its associated hand skills to elicit what these tell us both about human history, sociality and cognition, they developed new research pathways into the links between basketry hand-skills and cognition, including ‘hand-memory’ work for elders living with Dementia, enhancing recovery from brain injury or stroke, and exploring spatial and geometrical learning in mathematical education.

From 2010 onwards, Bunn worked with the Scottish Basket-makers Circle to reveal connections in what remains of traditional Scottish basket-making culture. The collaboration uncovered the names of historic makers of baskets in museum collections, the locations of their workshops, the materials they used, and the regionally distinct forms their work often took. Working with contemporary experts, they renewed intangible cultural knowledge in historical basket forms and uncovered the integral role of basketry in Scotland’s deep history.

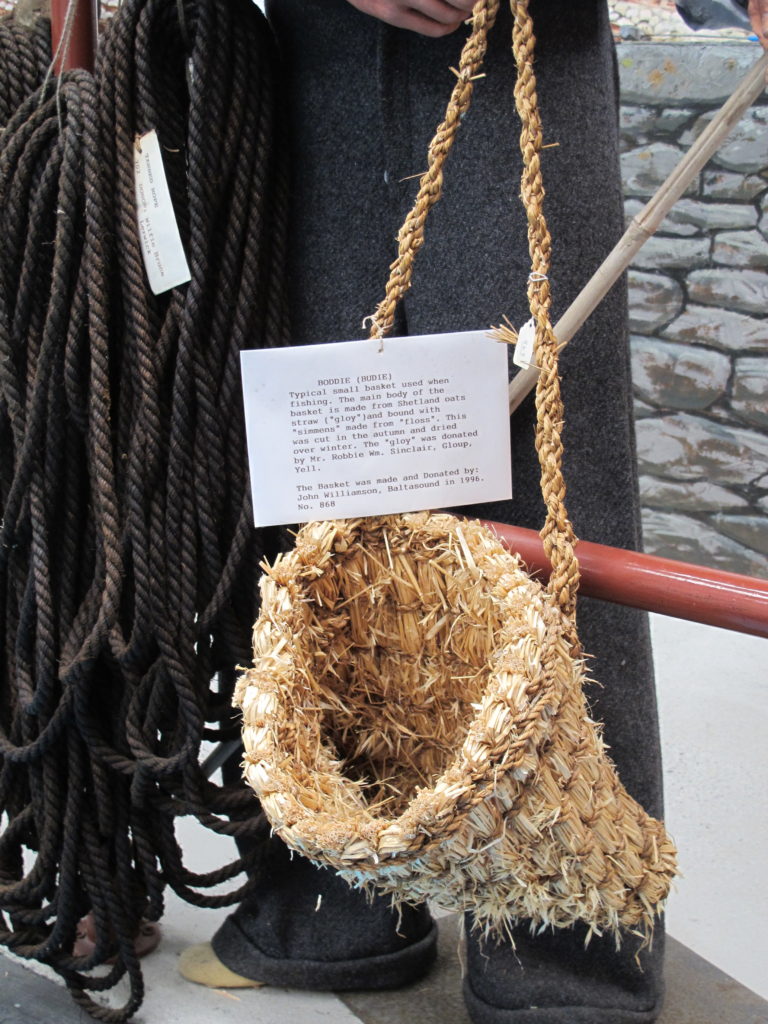

This work also revealed unusual materials that were not previously known to be used in basketry. The group linked these to past cultural influences and regional ecology, and highlighted how the materials for these baskets were gathered and processed. These included a ‘hair-moss’ basket from Roman occupation at Hadrian’s Wall, Celtic willow coffins from Iona, and Scandinavian docken and gloy (black oat straw) kishies, caissies and budies from Shetland and Orkney. It was found that each basket-form and local name reflected regionally specific ways of life: from crofting back-creels to fishermen’s quarter-cran herring measures and Lowland tattie sculls. Highlights included Western Isles murran horse collars, a WW1 basketry shell-casing transformed into a fish-trap in the Scottish Fisheries Museum, and a unique St Kilda puffin snare. The group’s work has informed at least 10 Scottish museum collections, revealing connections between collections, and enhancing understanding of basketry-linked social history across Scotland.

Stroke recovery

Earlier collaboration with the University of Hertfordshire’s Everyday Lives in War project led to research into how basketry can assist those recovering from shell shock and strokes. Working with hospital consultants at Raigmore Hospital Stroke Recovery Unit, Inverness, researchers developed structured sessions for patients with different capacities. The Woven Communities research showed that the bi-manual activity of basket-weaving promotes hand-to-eye coordination and attention development, encouraging the development of neuro-plasticity which can assist recovery in brain-injured patients, particularly stroke sufferers, where damage to one side of the brain affects the other side of the body. Staff reported improved patient concentration, insight, patience, and problem-solving. Three patients, who were not anticipated to be able to live unassisted, recovered sufficiently after the group’s work to return home. The activities also assisted with mobility, sense of self, and general wellbeing. The group has since published an online “Handbook for Headway” that helps to prepare volunteers for future work with stroke patients.

Dementia and memory

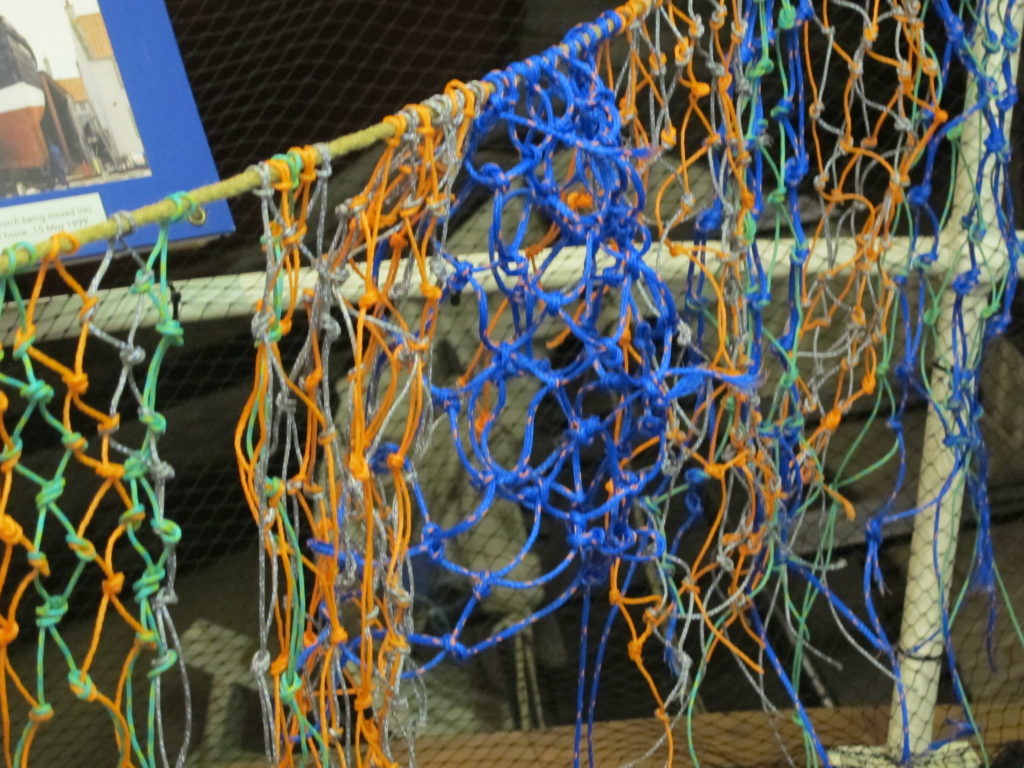

Collaborating with An Lanntair, an arts centre in Stornoway, the group’s ‘hand-memory’ work with dementia sufferers showed how hand-skills, such as twining straw and net-mending, often learned in youth, could be remembered decades later. The activities could evoke memories, both personal and cultural, by giving elders a bridge to their own history. Building upon this success, the project fostered intergenerational work between schools, care homes, and history societies that enabled people with memory loss to share their knowledge, providing invaluable information about the past to their local communities.

The work sometimes helped to provoke deeply significant personal breakthroughs. One dementia participant, who had not spoken for months, at one session said “The nets always break; you can’t help it. It’s a net mending needle… Hold it further back. No, not like that; like this, see? Watch me. Aye, that’s it… Yes, I did this. Every day… We were the best. We were good; we had to be. No room for mistakes… A hard life. All weathers. Everyday. No choice. But the seals would follow my boat, most days, and the birds. I liked that.”

Basketry hand-skills and mathematical learning

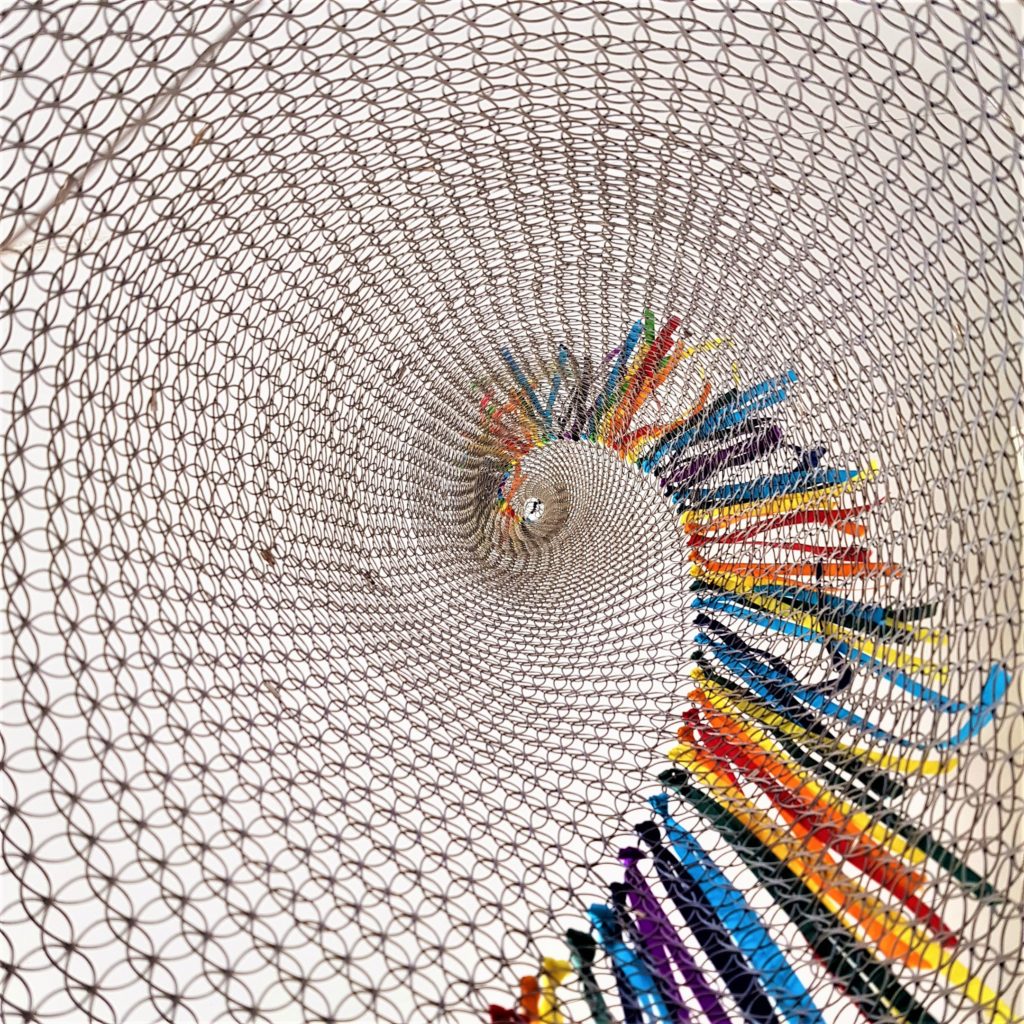

Contemporary developments in digitization and streamlining education can often emerge parallel to the perspective that many traditional craft-skills are no longer relevant. The Forces in Translation project has helped to dispel this notion by exploring how basketry hand-skills can enhance comprehension of, and provide a rich social context for, mathematical understanding, problem solving, and constructive, creative thinking. Through early maths and basketry research-engagement events, such as Tinkering with Curves (2018), collaborating with the University of Aberdeen’s Knowing from the Inside project, and with mathematical educationalist Professor R. Nemirovsky, the group demonstrated how basket-making can develop spatial and geometric understanding through the angles, curves, tension, and friction produced through gestural acts of weaving.

Working with Professor Nemirovsky from Manchester Metropolitan University and Professor Hasse from the Department of Future learning at Aarhus University in Denmark, and three basket-makers, the group explored how hand-skills are an essential complement to other forms of learning, of value for design, engineering, and maths work. This differs from the kind of responsiveness found in machines, where reactions may not involve memory, ideas, rhythm, constructive hand-work, or links between the material and the conceptual. Early trials have shown how using basketry-skills to explore mathematical problems, such as skewing, surfaces, curvature, or linearity, can provide additional insights to classical mathematical studies.

These findings benefitted from an extensive network of researchers that stretches from Peru and Jamaica to Germany and Canada, and which helped to spread the impact of their work. This includes a collaboration with Kew Gardens on the material and mathematical aspects of their Economic Botany collections, where the group drew on materials and forms from the Evolution Garden, the Palm House, and the Bamboo Gardens to explore the mathematics in different baskets in their collection. A collaboration with Ruthin Crafts Centre in Wales led to a residency project and four-month installation of their work, where members of the public were invited to participate in work investigating technique and colour in basketry patterning.

Looking ahead

Bunn has just been awarded a Leverhulme Emeritus fellowship to write a collaborative publication of the Forces in Translation research over the next two years. In addition, with assistance from the Basketmakers Association and Heritage Crafts Association, Bunn will soon develop work on a sister project to Woven Communities over the next few years that extends the influence of her work more firmly into England and Wales. This expansion will bring a project, initially focussed on Scotland, to focus on a UK-wide audience, amplifying the project’s already profound impact. The new initiative promises to adopt the best elements of citizen science projects, with basket-makers across the UK being involved in research linking with museums, and a raft of public events engaging and involving the public.