Banging the Drum for Samoan Cultural Heritage

Music plays an important role in Samoan culture and represents a complex mix of cultures and customs both from across its constituent islands and from further afield. Originally settled by people from the Lapita culture as early as 3,500 years ago, who established much of its traditional culture, precolonial Samoa saw frequent voyages to and from Fiji and Tonga that resulted in strong cultural and genetic links between the countries. Much later, colonial occupation under the German and British Empires saw dramatic shifts in almost every area of Samoan culture, including music. With the introduction of Christianity, western harmonies and instruments greatly influenced Samoan musical culture, adapting and sometimes even replacing traditional practice.

Recent efforts have focused on attempting to revive knowledge of customary musical instruments, which is quickly fading from the collective memory. The number of people who create or even remember customary instruments is reducing, and so recording this knowledge is a vital step in securing a cultural legacy for future generations to celebrate. One group that is playing an important role in this process is the ‘Recovering Samoan Instruments’ project, a collaboration between the National University of Samoa and the University of St Andrews. The project activities are led and guided by Susau Fanifau Konousi-Solomona and her colleagues in Music at NUS with the support of funding secured since 2018 by Emma Sutton, Professor of English at St Andrews and Associate of St Andrews’ Centre for Pacific Studies.

During 2020 and 2021, NUS researchers conducted interviews and focus groups with the goal of better understanding the process of customary instrument-making, as well as the contexts in which they were built and played. Instruments often had specific roles in ceremony, for example, or their customary use was limited to particular occasions or to one gender. In visits to over 30 villages, the project has recorded cultural knowledge about instruments and their significance, with trips to villages in the largest Samoan island, Savai‘i, being particularly successful. By recording the musical knowledge found across Samoa’s islands, the researchers hope to celebrate the heritage they find while retaining its diversity.

In addition to raising awareness of customary instruments, the project has commissioned new music and creative writing from Samoan artists, including from the distinguished Samoan composer Igelese Ete and from eminent writer Sia Figiel. Another element of the project is concerned with the more tangible elements of Samoan musical culture – the creation of a customary musical instrument, known as a logo.

What is a logo? (click to expand)

A logo is the largest type of Samoan slit drum, hollowed out from a single log chosen from particular species of native tree. A logo is an idiophone: instead of relying on a membrane to make sound, as do true drums, a logorelies on the resonance of the drum body itself when struck. The slits are cut into the top of the instrument, and the resultant alterations to the thickness and surface area of the instrument affect its pitch.

In his extensive studies of Samoan music, ethnomusicologist Richard Moyle identified four broad types of slit drum in Samoan culture, although all of these are subject to variation and have multiple sub-types. The smallest is the pātē, a handheld drum with a handle that is used primarily as a signalling device and occasionally as an accompaniment to singing and dancing. It was introduced from Tahiti by the London Missionary society, although the introduction of the handle and its uses are distinctly Samoan.

Medium-sized drums in Samoa are called lali, and are almost always played in pairs. Each pair has a larger drum, called the tatasi, and a smaller, called the talua. As with the pātē, the lali originated overseas, with both Tonga and Fiji having their own versions. The Samoan variant is distinguished by its smaller end sections. Similar in size to the lali is the nafa, although evidence for this particular drum is difficult to find.

The logo has a long, relatively straight body carved from a single log with a large slit; it is struck from the side with a large wooden beater. It is this drum that the project seeks to create.

Once complete, the logo will be housed at NUS, where it will be used in ceremonies at the University and for teaching in the Music Department and at the Centre for Samoan Studies. During the carving of the drum, which will take about two weeks, students will work with a team of instrument-makers to make smaller instruments while learning about their manufacture and the cultural knowledge associated with them. These instruments will join the logo at NUS; teaching resources on Samoan music are also being produced for use in primary and secondary schools, and for NUS’ community music education for children and adults across the Samoan islands. Recordings and other resources are being added to a bilingual website.

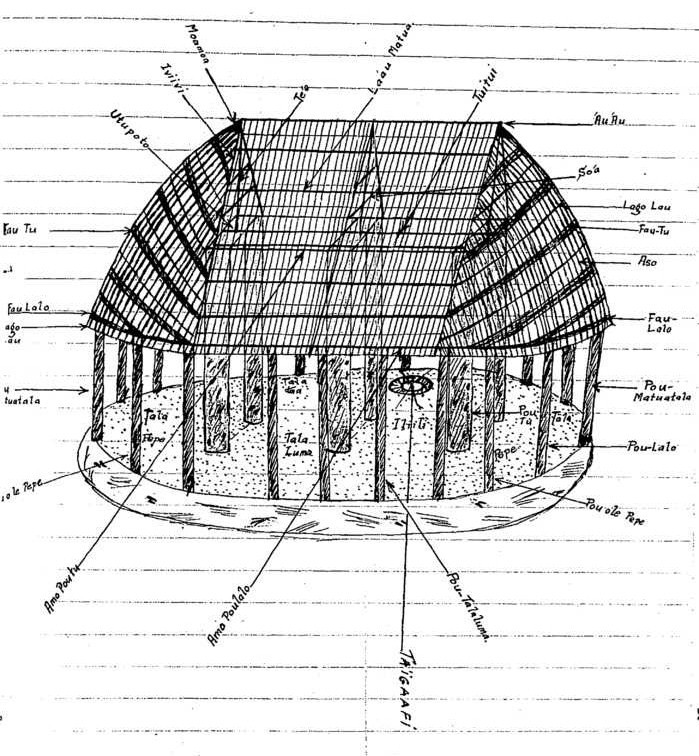

The logo will be housed within a newly built fale, a customary Samoan open-sided meeting house. Situated on the NUS campus, the fale is intended to foster and acknowledge the importance of the revival of Samoan customary instruments.

To date, the project research has featured in concerts and in four TV broadcasts in Samoa, giving the project a national audience. The project acknowledges with gratitude the village communities whose members have generously shared their cultural practices. Work continues to bring the project’s findings to an even wider audience within Samoa and internationally.