Prof. Katherine Hawley on Trust, Distrust, and Commitment

While we don’t trust/distrust everyone and everything we rely/don’t rely on; we rely/don’t rely on everyone we trust/don’t trust. Trust and distrust, therefore, seems to be reliance/nonreliance alongside something else. Hawley’s brilliance elucidates what that ‘something else’ is: recognising that distrust is just as important to consider when formulating the equation about our norms of trustworthiness.

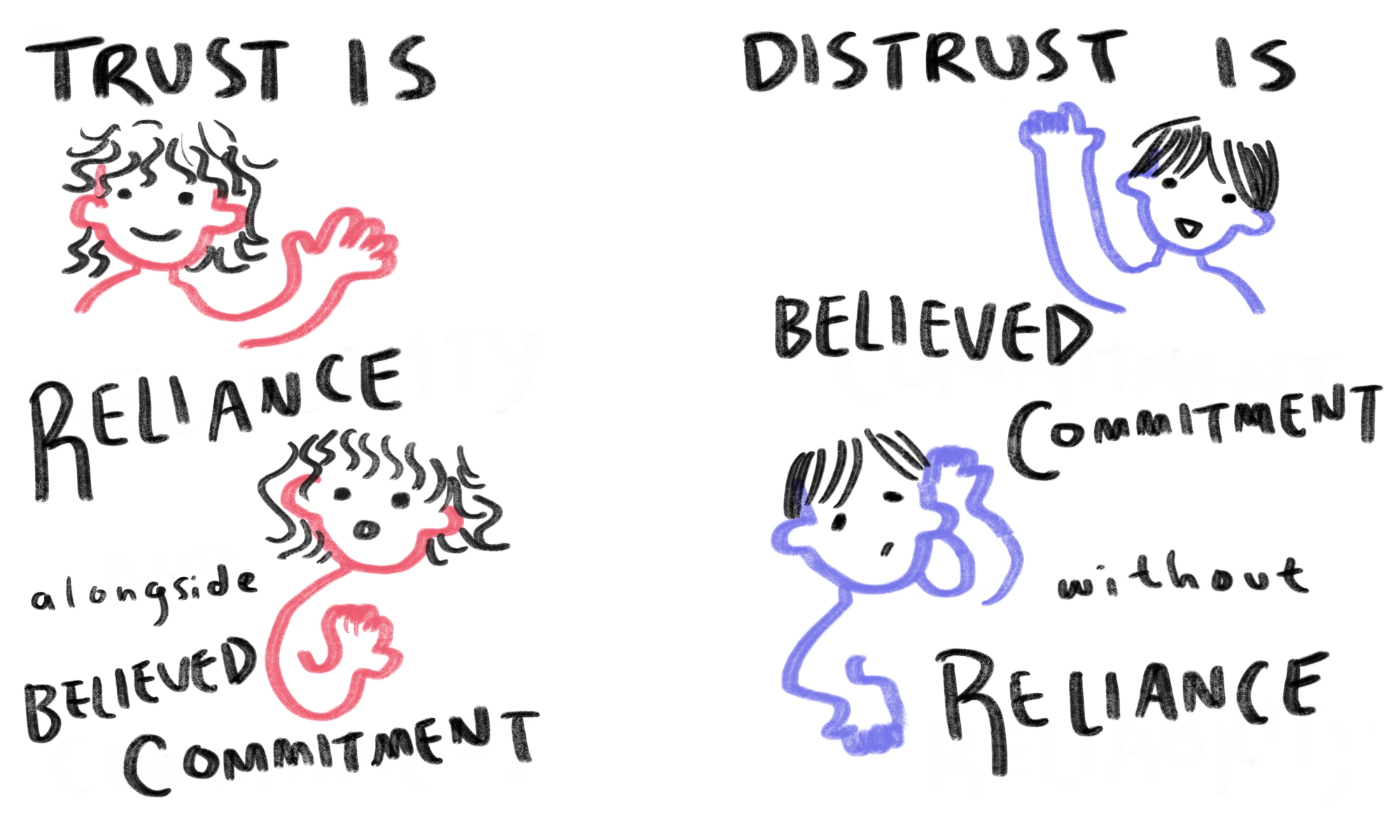

Hawley tells us that trusting or distrust someone to do something requires believing that they have a commitment to do that thing: trust is believing that they are committed and relying on them to follow through; distrust is believing that they are committed yet not relying on them to follow through. A politician who has committed themselves to act democratically but has shown themselves to be unreliable due to a history of corruption should not be trusted – while a doctor who has no commitment to giving me opioids should not be distrusted for suggesting other forms of treatment (of course, if he fails to fulfil his commitment to work in the best interests of my health, he does become untrustworthy: his commitment can no longer be relied on).

While we don’t trust/distrust everyone and everything we rely/don’t rely on; we rely/don’t rely on everyone we trust/don’t trust. Trust and distrust, therefore, seems to be reliance/nonreliance alongside something else. Hawley’s brilliance elucidates what that ‘something else’ is: recognising that distrust is just as important to consider when formulating the equation about our norms of trustworthiness.

Hawley tells us that trusting or distrust someone to do something requires believing that they have a commitment to do that thing: trust is believing that they are committed and relying on them to follow through; distrust is believing that they are committed yet not relying on them to follow through. A politician who has committed themselves to act democratically but has shown themselves to be unreliable due to a history of corruption should not be trusted – while a doctor who has no commitment to giving me opioids should not be distrusted for suggesting other forms of treatment (of course, if he fails to fulfil his commitment to work in the best interests of my health, he does become untrustworthy: his commitment can no longer be relied on).

Commitment here is broad, implicit and explicit, and malleable: your best friend might not have ever explicitly told you that they’ll support you in difficult circumstances – but due to the role they’ve come to play in your life, it would be correct for you to feel betrayed if they failed to show up when needed. Therefore, if you want to be trusted, make sure you go through with your commitments: don’t bite off more than you can chew, and don’t neglect your obligations (both explicit and implicit).

Hawley’s work on trust has had far reaching impact. Hawley has engaged with BBC Radio Science, Psychology Today, and large organisations to develop the Charted Institute of Insurers’ Public Trust Index: allowing insurers to measure their trustworthiness and giving them techniques to be trusted. Upon writing Trust: A Very Short Introduction, Hawley was invited to speak at the European Union, giving an expert seminar on how EU states can build trust amongst each other.

Hawley’s work, clarifying what trust is and why it matters, is an invaluable piece of philosophy she generously shared with the public. As an academic, educator, and person, she will be thoroughly missed.

Commitment here is broad, implicit and explicit, and malleable: your best friend might not have ever explicitly told you that they’ll support you in difficult circumstances – but due to the role they’ve come to play in your life, it would be correct for you to feel betrayed if they failed to show up when needed. Therefore, if you want to be trusted, make sure you go through with your commitments: don’t bite off more than you can chew, and don’t neglect your obligations (both explicit and implicit).

Hawley’s work on trust has had far reaching impact. Hawley has engaged with BBC Radio Science, Psychology Today, and large organisations to develop the Charted Institute of Insurers’ Public Trust Index: allowing insurers to measure their trustworthiness and giving them techniques to be trusted. Upon writing Trust: A Very Short Introduction, Hawley was invited to speak at the European Union, giving an expert seminar on how EU states can build trust amongst each other.

Hawley’s work, clarifying what trust is and why it matters, is an invaluable piece of philosophy she generously shared with the public. As an academic, educator, and person, she will be thoroughly missed.