Community theatre: the example of Classical Athens

The Athenians of the 5th-4th centuries BCE valued the performance of drama, as a mass art form and communal experience. They invested heavily in it too. Dr Jon Hesk, from the School of Classics, discusses how the example of Greek theatre can inspire young performers both to create their own original play and to passionately argue for the real social value of what they love doing.

‘We welcome spirits to the light!

We welcome spirits wrong or right.

We dig down deep inside the earth

And drag up something to judge its worth.

We chant and shout and screech and scream.

But we do not appear as we first may seem.’

Where do you think these lines of choral chanting come from? A Penguin translation of Aeschylus or Euripides, perhaps? Or one of the many versions and reworkings of Greek tragedy which have been produced by various celebrated poets and playwrights of the 20th and 21stcentury?

Well, you’d be forgiven for either of these guesses. But they’re actually taken from the very start of an original play called Hamartia. This work’s title was inspired by Aristotle’s word for the mistake, error or flaw of personality which often lead the main characters of a Greek tragedy into terrible suffering. The play was devised and performed by members of Byre Youth Theatre Ltd.’s Adult Collaborative Performance Group. Byre Youth Theatre Ltd is a non-profit organization providing exciting opportunities and training in drama and song to children and young people in Fife. The organization has close links to the recently re-opened Byre Theatre in St Andrews.

From September 2016-June 2017, I and my colleague Dr Ralph Anderson worked with this group of performers – four young local people aged 17 and above – and their teacher from BYT Ltd., Stephen Jones. Stephen is a specially trained and experienced theatre practitioner. The group met every Thursday evening in the school term.

The project was called ‘Greek Drama in the Community. Working with the Byre Youth Theatre towards a devised performance’. Designed by Stephen, myself and Ralph, it was funded by the University of St Andrews’ Knowledge Exchange and Impact Fund. Alongside the final goal of helping these young people to create their own short piece of theatre, its key aim was to explore how the content, context and conventions of ancient Greek tragedy might be used to inform and inspire the group’s work. The performance itself was a great success and we hope that our experiences and documented findings will prove useful for anyone contemplating similar ventures. Whether you work in the professional theatre, a local ‘amateur’ group or in theatre education I think our project offers some valuable lessons and ideas. The model of combining ‘academic’ briefings and Q & A sessions alongside more practical workshops and brainstorming sessions proved very successful. But it was also crucial to think of ancient tragedy’s conventions and themes as resources for the group’s own creative imaginations and onward learning rather than as a restrictive template for them to emulate or apply. And the project only worked because Ralph and I let the group tell us what they wanted to know about, rather than imposing upon them our preconceived ideas about what they ought to know.

I learned my first important and surprising lesson in my initial meeting with the group back in September 2016. (This was before we had even fully decided on the project’s goals). Stephen knows a good deal about Greek theatre, having studied it (among other things) at university. But the group itself only knew a few bits and pieces. So, I had come prepared to give them an overview of the context and conventions of Greek drama and I’d also got some answers to questions which they’d sent to me in advance: why did the Greeks not have female actors and chorus-members? How was gender depicted on stage? How were masks used? How did gods appear? Why was violence generally kept off stage in Greek tragedy?

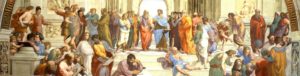

These were all good questions and I did my best to answer them. But it was during the initial overview that things took a surprising turn. I was explaining that Greek drama was central to the Athenian religious festival calendar; that it was a mass art form watched and enjoyed by thousands of citizens; that the Athenians put huge amounts of money and organizational effort into putting on these plays; that great prestige and honour attached to those wealthy citizens who funded a winning chorus; that the choruses were trained-up ‘amateur’ citizens and that many audience members had experience of being in the plays themselves; that theatre was clearly integral to the culture and values of the Athenian citizen-state (the polis). I paused for breath and fumbled with my laptop to find some suitable images. Stephen jumped in and asked the group what they thought about everything I’d said so far. How did it compare with their experience and understanding of what theatre is now?

The group had many diverse and differing opinions but they were all vehemently agreed on one thing: theatre just isn’t valued by their own society in the way that it was for the ancient Athenians. They didn’t see modern theatre as a mass art form and they were largely sceptical about my counter-argument that popular drama is still valued as a cultural and communal experience (thanks to cinema, television and online streaming services). For all that films and TV series can say something important and complex about our society, politics and values, they said, the fragmentation of audiences and the sheer quantity and variability of content meant that they weren’t anything like the communal experience of an Athenian dramatic festival. And they argued that this communal experience had value in and of itself.

This wasn’t a detached, purely intellectual debate for the group. Their view that live theatre is not a popular art form and is not properly valued was a matter of deep regret and intense personal feeling for them. The sociology of Athenian drama had offered them a means of discussing how marginalized and undervalued they felt as young people with a real commitment to drama. It wasn’t that they were idealizing classical Athens and its tragedies and comedies, either. They knew about its use of slavery and its exclusions and restrictions on women and foreigners. Their point was that this society produced great theatre through a commitment and appreciation which was both deeply held and genuinely ‘community-wide’. The fact that the Athenians were prepared to spend so much time and money on communal religious festivals and theatrical art highlighted the comparatively diminished status of the performing arts and ‘community theatre’ in the UK today.

Before that meeting, I had a rather prosaic reason for giving the title of ‘Ancient drama in the community’ to our overarching project. If the mission was to bring my department’s research and expertise in Greek and Roman drama out of the academy and into the wider world, this title seemed like a simple and effective description of that goal. What I now realize is that the socio-political centrality and cultural embeddedness of Greek and Roman drama – aspects of which are key to my own and colleagues’ research – are themselves important and salient items of evidence to bring into public debates about the social and political role and value of live theatre and dramatic culture at large.

The city of Athens and the surrounding demes of Attica developed a form of ‘community theatre’ which genuinely brought the mass of citizens – the ‘people’ (‘dēmos’ in Greek) – together to participate in it. Drama flourished in tandem with this community’s new and developing democratic constitution. So Athens’ culture of mass participation in the making and watching of plays didn’t just produce all those great works by Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes. It forged a strong sense of communality and community by focusing citizens’ minds on shared values, tastes, and commitments, not to mention shared problems and areas of conflict. Athenian theatre offers us a powerful image for how the valuing and nurturing of live theatre could strengthen our own communities.

Dr Jon Hesk, School of Classics